Ex 1.11 Read the extract from a book. Check the meaning of the words in bold in the glossary (Appendix 2) if necessary.

BACTERIA

Bacteria are individual living cells. Bacteria cells are similar to your cells in many ways; yet, they also have distinct differences. Bacteria have many unique adaptations allowing them to live in many different environments. Bacteria are perhaps the most adaptable life forms on earth. And, for this reason, are the most successful organisms on the planet. They lived on this planet for two billion years before the first eukaryotes and, during that time, evolved into millions of different species. The tiny microbes survive and thrive in virtually every environment - from the black abysses of the oceans to the icy deserts of Antarctica to the thin upper atmosphere. Scientists have even found bacteria living miles underground, where they feed on radioactive rocks. Their amazing capacity to adapt and carry on helps explain why these microscopic, single-celled organisms make up a good chunk of the biomass on Earth. On a more personal level, bacteria not only live all around us but on us and inside us as well; they also inhabit our food. The vast majority of bacterial species are harmless to humans. But given their extraordinary variety of forms and survival strategies, it's little wonder that a few bacterial species are human pathogens and that some of those can be transmitted by food. To understand how the more important malefactors, such as Salmonella enterica, Listeria monocytogenes, and Escherichia coli 0157:H7, can sicken you and those you cook for, it helps to have a good working knowledge of the major kinds of bacteria and their life cycles. Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli are commonly involved in infections of both community and healthcare settings and are amongst the leading causative agents of food-borne infections worldwide.

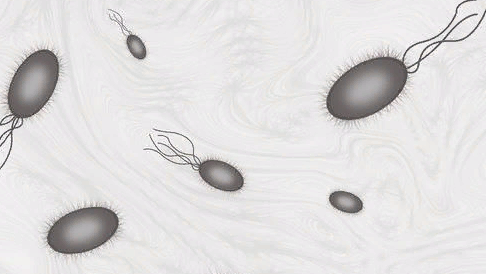

An individual bacterium is so small that (with only a few exceptions) it is invisible to the naked eye; you need a microscope to see one. E. coli is typical in measuring from two to three microns (millionths of a meter) long and about one micron across. Thus, it would take something like a million E. coli laid end to end to equal the height of a tall person. Bacteria don't weigh much individually, either - perhaps 700 femtograms each. You'd need to assemble about 1.5 trillion of them to tip the scale at 1 g I 0.04 oz. But what they lack in girth and mass, they make up for in numbers. Under the right conditions, bacteria can multiply overnight by a factor of one thousand, one million, or even one billion. People sometimes liken bacteria to microscopic plants, but in truth these minute organisms have no direct analog in the macroscopic world. They really are a distinct form of life. Unlike viruses, bacteria are fully alive: they absorb nutrients from the world around them and secrete chemicals back into it. And many species are motile, or able to travel under their own power. Bacteria that move often do so by spinning one or more tail-like appendages, called flagella (Figure 1) that contain complex molecular motors.

Figure 1. The structure of flagella

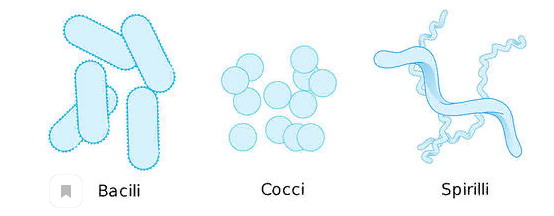

Flagella help bacteria move. As the flagella rotate, they spin the bacteria and propel them forward. It is often said the flagella looks like a tiny whip, propelling the bacteria forward. Though some eukaryotic cells do have a flagella, a flagella in eukaryotes is rare. The flagella facilitate movement in bacteria. Bacteria may have one, two, or many flagella - or none at all. The coordinated rotation of these motors propels the bacteria at surprisingly fast speeds. Other common adaptations, such as the ability to form protective cell walls and spore cases, as well as the capacity to aggregate in large groups, have contributed to both the ubiquity and the staying power of these ancient organisms. Some species, called aerobic bacteria, need oxygen to survive just as we do. Surprisingly, oxygen can be a deadly poison for many others, known as anaerobic bacteria, which have evolved to live in air-free environments. Some bacteria tolerate oxygen, but only so much at vey low concentrations; scientists refer to them as microaerophilic. Yet another category of bacteria can live in either anaerobic or aerobic conditions; specialists call them facultative anaerobes. Apart from the microbe's living arrangements, researchers classify bacteria by their physical chemical, or genetic properties. In the early days of microbiology, bacterial classification relied mainly on visual characteristics-rod-shaped bacteria were distinguished from spherical (coccal) or spiral varieties, for example. Bacteria are so small that they can only be seen with a microscope. When viewed under the microscope, they have three distinct shapes (Figure 2). Bacteria can be identified and classified by their shape:

Bacilli are rod-shaped.

Cocci are sphere-shaped.

Spirilli are spiral-shaped.

Figure 2. Scientific classification of bacteria

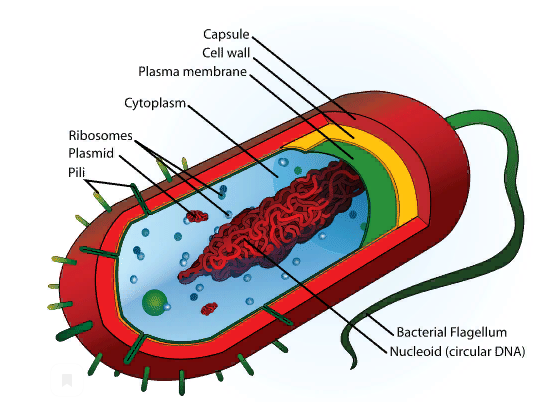

Similarities to Eukaryotes. Like eukaryotic cells, bacterial cells have:

- Cytoplasm, the fluid inside the cell.

- A plasma or cell membrane, which acts as a barrier around the cell.

- Ribosomes, in which proteins are put together.

- DNA. By contrast though, bacterial DNA is contained in a large, circular strand. This single chromosome is located in a region of the cell called the nucleoid. The nucleoid is not an organelle, but a region within the cytoplasm. Many bacteria also have additional small rings of DNA known as plasmids.

The features of a bacterial cell are pictured below (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The structure of a bacterial cell

Unique Features. Bacteria lack many of the structures that eukaryotic cells contain. For example, they don't have a nucleus. They also lack membrane-bound organelles, such as mitochondria or chloroplasts. The DNA of a bacterial cell is also different from a eukaryotic cell. Bacterial DNA is contained in one circular chromosome, located in the cytoplasm. Eukaryotes have several linear chromosomes. Bacteria also have two additional unique features: a cell wall and flagella. Some bacteria also have a capsule outside the cell wall.

The Cell Wall. Bacteria are surrounded by a cell wall consisting of peptidoglycan. This complex molecule consists of sugars and amino acids. The cell wall is important for protecting bacteria. The cell wall is so important that some antibiotics, such as penicillin, kill bacteria by preventing the cell wall from forming. Some bacteria depend on a host organism for energy and nutrients. These bacteria are known as parasites. If the host starts attacking the parasitic bacteria, the bacteria release a layer of slime that surrounds the cell wall. This slime offers an extra layer of protection.

Later on, investigators began using chemical dyes, such as Gram's stain, to distinguish different classes of bacteria by the makeup of their cell walls. These days, scientists classify bacteria primarily through their genetic properties by sequencing their DNA.